Today is my last full day at McMurdo Station. Tomorrow, weather permitting, I will board a C-17 bound for Christchurch and begin the next adventure. My five months here have been everything I could have hoped for, and summarizable simply as ‘an experience.’ I haven’t written anything in almost two months, but not for lack of things to write. On the contrary, by the time Christmas rolled around, in my mind I had planned material to last me the entire season, and from there on forward there was plenty more that came my way. The bars and coffeehouse deserve their own post, as do my coworkers and the things I did as a shuttle driver. The living creatures that inhabit this cold continent – penguins, whales, seals, skua… especially the skua – were all engrossing and welcome signs of life around the station and driving the Plagusus road.

By the way, by the end of December, the road to Pegasus had become much more driver friendly; with the constant presence of vehicles packing the road down, it turned into a veritable highway, where the primary difficulty was sticking to the speed limit of 25 mph. Well, there were still a few treacherous spots now and then…

The flow of life on the station was always fascinating, and the slow, subtle grinding that accumulated as long hours, confined spaces and an isolated population began to take their toll made for a case study in social dynamics. I wish I understood it all. For myself, I am a little relieved to have completed it. I am thankful for the people I’ve met, the things I’ve been able to do, the views I’ve seen. There is more here to explore, and there is more I would do were I to return. And it’s a place where I feel quite comfortable. I could do it again, and be happy. That said, it’s not a place I could be continually. The fact that with the completion of a summer season we contract workers are obligated to leave is necessary because the pace we set is too hard to do year round. Maybe for other people, but not for me. I like to go full bore until I am exhausted – until I’ve fulfilled the goal – and then step back and reset. I feel like I’ve accomplished that.

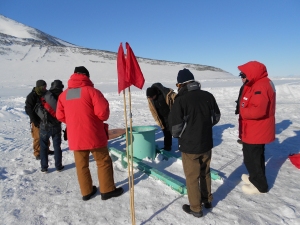

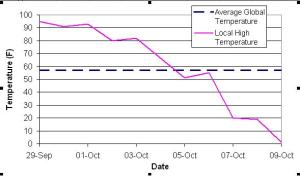

Speaking of going until I have nothing left, I managed to accomplish a life goal while I was down here! I participated in a marathon. What a thrill. What a miserable, cold and lonely thrill. I finished it half limping, unable to walk straight, with my knees battered and my quads cramping. It was masochism, and it was – admittedly – madness. At the end there was nothing left in my legs and I was exhausted. There were times in the 18th mile, the 19th mile, the 20th, 21st, 22nd, 23rd where I didn’t know how I was possibly going to finish, how this was probably a mistake and how making it to the next flag along the road – with each red flag on the snow road a mere 100 feet apart – was going to be a challenge. There were over 500 flags that I passed that day. I never wanted to do anything like it again. I was completely and utterly devoid of any desire to do it again. And that feeling, that total exhaustion, somehow made it fulfilling, because I had given pretty much everything my body had to offer on that day and subsequently gotten everything I could have out of participating. Such are the confusing glories of life.

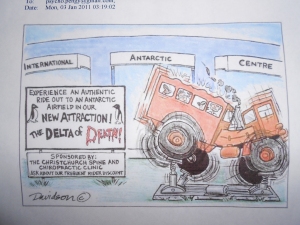

Some time prior to Christmas there was a gingerbread house building competition. Shuttle Elisha organized a shuttles team with myself, Shuttle Mel and Shuttle Guy. Arriving at the dining hall, we ran into Fuelie Turk, who is a friend to shuttles, and we invited him to join our team. He provided much camaraderie, creativity and fun. There were 8 teams competing with the goal of, nominally, making a gingerbread replica of Discovery Hut. To that end, the gingerbread pieces had been baked into the necessary shapes required, with triangular wedges to make the roof and rectangular ones for the side. Few of the teams had any intention of following the cookie-cutter blueprint.

Naturally, as shuttle drivers, our gingerbread creation was going to be shuttle themed, and it was quickly settled that we would make a delta. Of course, we made that decision on the spot, as the two-hour time limit was beginning. So much for planning ahead! Surveying our construction material, we found all kinds of sweets: candy canes, red-hots, ice cream cones, mint chips, cookies, frosting, food coloring. Our construction took shape as parts of the delta were fashioned: front cab, passenger cab, wheels, engine compartment. Into the frosting red and yellow food coloring was combined to make a convincing orange for the paint job. To add to the scene, the ginerbread base on which the delta was to be mounted grew up with little flags, pressure ridges and penguins in order to mark ‘The Road to Plagusus.” The wheels were secured to the ground, and carefully, delicately, the unbalanced, top heavy monstrosity was placed and frosted into place. What resulted was, if I may say, an engineering feat that very properly conveyed the cantankerousness of a real delta. We all had a great time.

I hope to post a few more anecdotes for posterity, but for now it suffices to say that this place, like so many places where you take the time to appreciate it for what it is, was wonderful and unique. I feel pretty good that Igotthis place, which really was the whole point, after all.